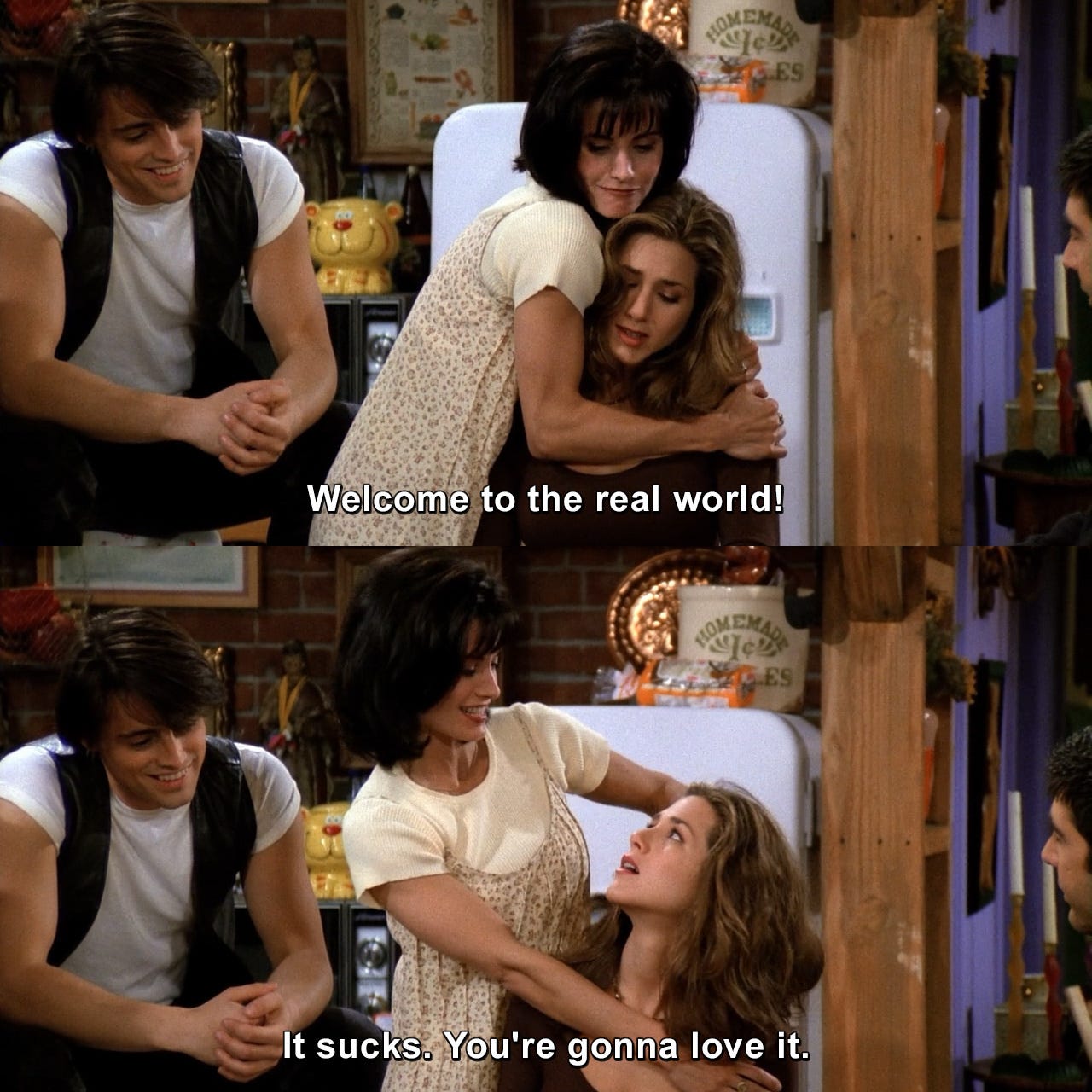

“It’s the end of an era,” Monica says to an indifferent Rachel who is about to move out of Apartment 20 so that Chandler can move in. Rachel replies, barely looking up from painting her toes, “I don’t think six years counts as an era”.

“An era is defined as a significant period of time,” Monica snaps in apparent frustration as she tries to draw out emotion from Rachel. After a little bit of a heartfelt exchange, Rachel finally accepts the salience of her impending departure, and exclaims in grief, “It is the end of an era!”

Last night Matthew Perry died, and I found out, strangely enough, through a comment someone published on one of my sailing YouTube videos. It started with “I’m sorry to have to tell you this, but”. Of all the different online platforms I exist on, even the area of the internet that I think knows me the least, knows my love for Friends. I regularly quote lines and include clips in our videos. Our dinghy is named Chandler.

Those who actually know me know that my vocabulary is filled with words and phrases like wisdomous and moistmaker and supposably and moo points and WENUS, I respond in facial expressions like Ross’ when he finds out Rachel’s pregnant, I have friendships that have mostly been built upon a shared love for the show, and our wedding vows even (obviously) included Friends references.

Those who know me also know that my love for the show is about far more than just the show — it’s about where the show lives in me. It lives in the purple walls of perfect, cozy nostalgia, where everything is basked in the warm glow of sentimentality. The excellent writing and its impeccable delivery, after I have watched and rewatched to a degree that surely most would find horrifying, offers a familiarity that feels like the sensory equivalent of home, of childhood, of a blanket being wrapped around me by someone I love, of roaring fireplaces and a cup of tea and those increasingly rare moments when all problems seem to disappear and contentment quietly moves in and everything is ok.

Because of this, I (still) use the show as medicine, reaching for it in the times I find the severity and complexity and sheer weight of life to be too heavy, when I want just the slightest distraction, the tiniest relief, the briefest opportunity to just pretend that everything is ok. Putting on an episode brings me instantly back to a time in my own life — my teenage years, when the show first aired, when I watched it all for the first time — where life certainly felt like a lot, but retrospect reveals its relative simplicity.

I cringe a little at the cliche of thinking this, let alone saying it out loud, but the truth is that for me and for countless others, the show actually feels like I am hanging out with my real friends, temporarily gifted the permission that comfortable friendships always grants us to linger in levity, to relish in our in-jokes, to forget about the burning world for just a minute while we tease each other and make fun of ourselves and concern ourselves with our stupid little lives and our silly little problems, like trying to find a job that doesn’t suck or learning how to fail at something or navigating the changing landscapes of relationships or how to grow up.

These days it’s common for the show to be criticized as deeply problematic, and rightly so, with nearly every episode revealing some glaring ignorance in how the characters see the world or relate to their own, or other’s, sexuality, from Ross refusing a male nanny to Carol’s queerness being the butt of all jokes to Rachel’s deplorable “A-man-duh!” comment about Chandler’s dad to everyone mocking Joey’s “man’s bag”, and the list goes on and on. Charlie Squire’s essay on similar criticisms of Sex and the City puts these projects in an interesting, and important, light:

Sure, if an individual doesn’t want to watch a show where the main characters say things that are terrible and mean and gauche, they shouldn’t watch it. But to say that something is valueless because it doesn’t align with our current morality is to throw away the most important archives we have. Media that is “politically incorrect” or “dated” is media that is honest, it is media that is made by real people that reflects their real values. Those are the values that are often subconscious or unexamined, things we can only see with the lens of a decade of reflection, but they are also the values that drive politics, elections, and policy. It is exactly because Sex and the City was not made to be read politically that it is so politically valuable, it is rich with the real-life politics that would have otherwise been written out if producers thought they were detectable.

Friends, too, is an honest archive. It is the ‘90s, it is six totally flawed and mostly awful people, it is all of us in one point or another in our lives, trying to do and be good but also missing so much about what that actually asks of us, it is a reliable mirror that we can use to be able to see just how much we have grown, as a culture and as individuals.

I always thought it was interesting that every time I rewatch the show, (which I do, start to finish, about once a year, and it still makes me laugh out loud), the characters I love the most or that I judge the most, change. Chandler was my favorite for a long time. Snarky, skeptical, sarcastic, scared. This was how I moved through the world in my teens and most of my twenties. Pushing people away, never wanting to get too close, constantly making the wrong choices and making it all into jokes, riding an undercurrent of chronic self judgement and disdain that felt private but was probably palpable and obvious to everyone around me, just like Chandler. These days I align most with Phoebe (someone who used to drive me mad), and I see Chandler as sad — someone caught in pain who doesn’t know how to help himself. And though I never really learned too much about the real people behind the sitcom, I know that this might be a fair assessment of not just Chandler, but Mathew Perry.

Helen Lewis shared a beautiful piece on Perry, only hours after his death:

I met Matthew Perry once, in the early 2000s. He came to Oxford, my university, to speak at the Union. During my own twenties, I used to joke that meeting Perry was the day my adolescence ended: that I said hello to this icon of my teenage years, this idol who had meant more to me than anyone I had dated during that time, who had left his fingerprints in my clay for life . . . and discovered that he was just a man. Sarcastic, insecure, anxious. Perry walked into the Union chamber, looked at the huge crowd and said, “Could there be any more people here?”

He gave us what we wanted. . . and I hated it.

I never cared to learn much about the actors behind the scenes because I knew on some level that this what was in store: a let down, some of the magic getting taken away. Any facts I know about their lives are purely accidental (like Jennifer Anniston actually dated the character Joshua in real life; Lisa Kudrow majored in biology and discovered acting through Jon Lovitz (who had two separate appearances on Friends); one of Anniston’s best friends made a cameo as Megan in the episode where Monica is wedding dress shopping; Mathew Perry battled an addiction through nearly all of the show’s ten years on air that was so severe, he doesn’t remember filming several seasons of it).

This is all some trivia I stumbled on somewhere, nothing I ever sought out to know, because to me, the real value of the show was in the show, not in the dramas of the real lives of the real people who made it, and the more I knew about them, the more of the show’s personal preciousness could potentially wither away. I refused to watch the Friends Reunion they made in 2021 for this same reason. Maybe it’s stupid, but the thought of seeing them all, now in their 50’s, worn by decades of real life and punishing fame, sitting against the unchanged and vibrant set as some sort of harbingers of the reality of age and time and our own creeping mortality, seemed like something I’d rather not see, like it somehow would tarnish the brightly colored role the show plays in the arc of my own life.

And maybe through these efforts, or maybe through my general, genuine and enduring love of the show, even with all its flaws, it has managed to stay perfectly preserved to me, enshrined in the idealized pastel colored glasses of childhood and adolescence, which is to say that the part of me in which the show lives, the timeless and sacred and hopeful, in all its youthful and wistful ignorance, has managed to stay just about perfectly preserved. Until last night.

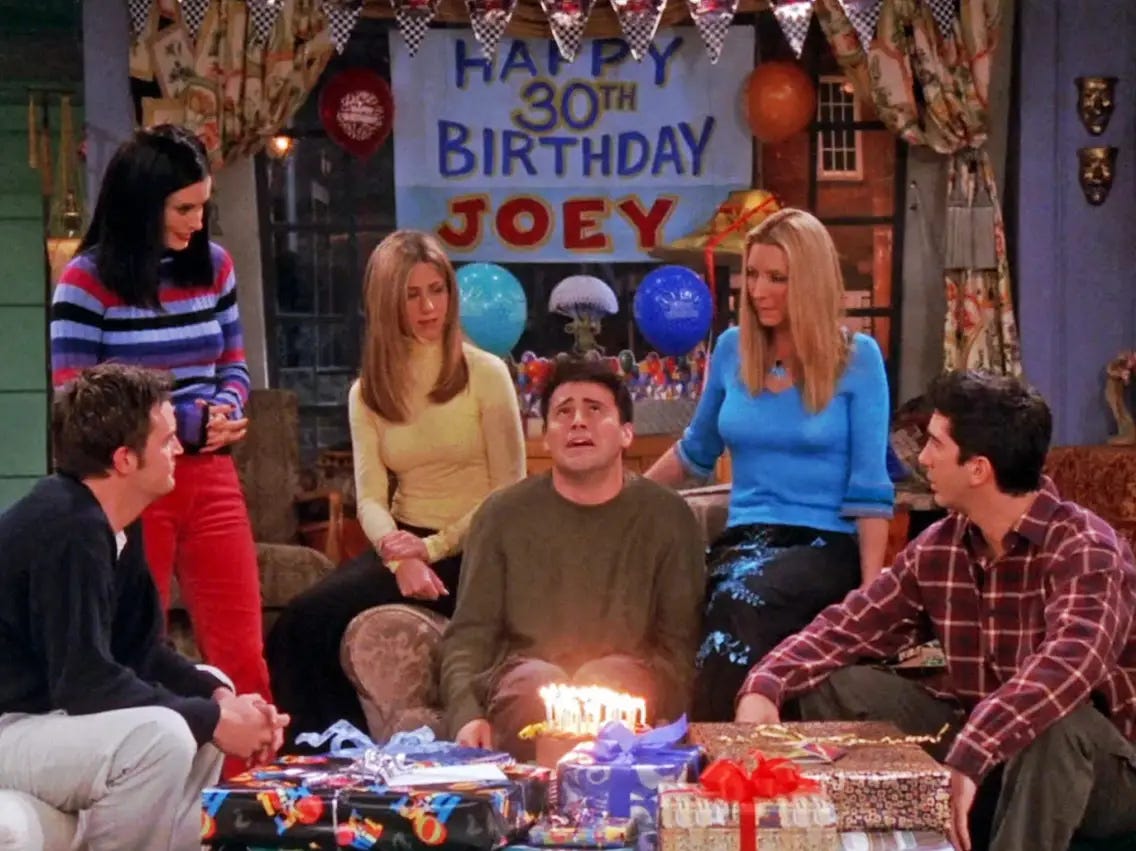

Listen, I know we’re all going to die and I do much work within myself, daily, to meet this fact with acceptance and openness. But amid all the brutality in the world and the painful losses that we all endure or will soon endure, all the change that is thrust upon us, all the upheaval and uncertainty and awfulness, the one place that has stayed steady and unchanging and reliable in its ability to land me immediately in laughter and delight and familiarity and peaceful predictability — this silly little tv show — has now been changed.

The show is still here, I know. But if Friends is the sensory equivalent of home and childhood, then Perry’s death is the reminder that we can’t stay home or be children forever. This too, I know. But when this fact becomes burdensome and too much to bear, as it sometimes can, this show was and is one of the ways I protect my inner child, the part of me that flatly refuses this fact, the part of me that longs for something soothing and eternal and unchanging and uplifting — and it always, always delivers. And now, with the first death of what will eventually be all six of them, this protective power seems to have been altered, cracked, by a sudden and harsh reminder that time is coming for us all. (Why god, why?! Why are you doing this to us??!)

And maybe that’s why this news is so sad to me. Not just because Perry’s death was too soon and tragic, but because his character is a part of history, a part of my history, encoded into and tied to the seasons of my life, my memories, of what I hold dear, of what I fear, of how I’ve grown. Because he is part of something purely fictional that represents something very real and significant to me, and his real-life departure from this world has changed the way that that something lives in me.

It is the end of an era.

xo,

Taylor

I am so happy to have found someone else who relates to Friends the way I do. Actually, just this week, I shunned this part of me, called it “immature and idealistic” and stopped watching tv shows all together.

I teleport to TV shows so easily, I can lose touch with my reality.

But reading you, I see there’s a beautiful way of doing it, in moderation, where I can tap into the familiar, cosy sense of safety and home that the show gives me. I can relax, sink into the couch: I’m home with these guys.

So, thank you for saying these things. Reading your words gave me permission to reintegrate that part of me, not repudiate it.

This was beautiful Taylor. Thank you.